Boost your thesis writing!

- The Brainy Knitters

- Dec 16, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 28, 2023

A workshop with systematic brain breaks

Writing a thesis can feel like a mental marathon and requires long sessions of reading and writing. Staying alert and focused for long hours is crucial, but sometimes things take a turn, and all of a sudden you find yourself not productive anymore and consistently making mistakes. Have you ever felt like your focus is fading gradually, and mental fatigue is hindering your progress? Worry not, you are not alone.

Research shows that as time goes on, our focus tends to drop, leading to distractions, lower performance, and just feeling exhausted. Sounds familiar?

The main strategy we are using to maintain performance and stay on top of the game, is to increase our effort, so we can cope with the fatigue from mental tasks. Yet, this extra push is triggering stress responses in our body like a rise in blood pressure or release of epinephrine. Not a good strategy!

The art of taking breaks

The good news is that science has offered a game-changing strategy to help us recharge our cognitive batteries. The remedy that scientific studies suggest is to 'take breaks'. A break is essentially defined as "an interruption of a task with the aim of recovery." This simple yet effective tactic works like magic, especially when it comes to tackling mentally demanding tasks commonly found in our academic endeavours like writing a thesis :) The impact of the art of taking breaks becomes more obvious when we have to study for extended periods (which we do in most cases). The studies also show that taking a breather helps us to stay focused and engaged in the task at hand.

Now, let’s get more serious to figure out how breaks are helping us: Recent studies in neuroscience have dug deeper into how taking breaks can actually boost both how we perform and how our brain ticks. Thanks to tools like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), researchers can monitor inside the brain and see how it changes during moments of rest, and guess what? Our brain functions totally differently during rest breaks and while performing a challenging task. Neuroscientists noticed that when we take a break, some areas in our brain like the prefrontal cortex inactivate. This simply means that we have given some recovery time to our brain, so it can recharge and start working on our intense cognitive tasks.

So, next time you are buried in piles of articles or writing your research discussion, keep in mind that taking a break is a golden strategy, proven by science, to rescue you from thesis challenges.

But what if, you already take random breaks? Like the pauses in which you use your phone, read or eat and sometimes end up entering in procrastination cycles. Having this same experience, lead us to question, "which types of breaks can be more effective and give us the benefits explained before?" In this blog post, we recommend you to have systematic breaks that combine the benefits of physical activity, music and the Pomodoro Technique. Tag along to learn more and put it into practice with the workshop you´ll find at the end of this post!

Move your body in the breaks

Engaging in physical activity has incredible benefits on your brain's well-being. The evidence supporting the positive impact of exercise continues to grow. As highlighted in psychiatrist, Anders Hansen's book, the benefits of moving your body range from enhanced concentration and better memory to increased creativity and resilience to stress.

So, what's the magic behind these brain-boosting effects?

Neuroscientists found that physical activity activates the prefrontal cortex, a brain region crucial for focus and attention. Moreover, through a process called neurogenesis, exercise stimulates the growth of new brain cells in the hippocampus, enhancing long-term memory.

Now, if you're under the impression that these benefits come only from regular physical activity over a few months, think again! The good news is that short-term physical activity, even a single workout, could make a difference. Only 5 minutes on the treadmill can increase the hippocampal theta waves, while a 10-minute cycling session can enhance prefrontal cortex activation. Time is no longer an excuse – even a burst of exercise could power up your brain. Elementary school students get better math fluency after a mere 5-minute walk – imagine what it could do for your thesis work!

Neuroscientist, Wendy Suzuki, in her TED talk, sheds light on the immediate positive effects of exercise on the brain. Perhaps, the most noticeable of these is the mood boost. A single bout of exercise sparks an immediate increase in neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine, known to enhance mood and reduce stress. So, when the pressures of thesis writing weigh heavy, consider a brief exercise break for an instant mood lift.

Besides the happy mood, an acute exercise can also improve your cognitive performance. In a revealing experiment, light-intensity physical activity proved to enhance university students' cognitive performance, particularly their ability to shift tasks. This means you will think faster and more efficiently after a brief exercise session.

In essence, the takeaway is clear: physical activity, even in short bursts, yields immediate and tangible benefits to your brain. Every move counts. Taking a short, light-intensity physical break can recharge your mental battery without leaving you exhausted. Given this, we believe that physical exercise could be one of the perfect options for our break activities.

Tune into Music for a Refreshing Break

Have you ever heard of the Mozart effect? Three decades ago, scientists found that after listening to Mozart piano sonata, people got temporary higher scores on spatial reasoning. While exposure to the sounds of Beethoven can have similar effects, the Mozart effect indeed indicated the potential benefits that music can have on our brains.

In fact, the profound impact of music has been demonstrated in the realm of neuroscience. For example, music is a powerful stress reliever, as relaxing tunes have been proven to help reduce heart rate and stress hormone secretion. Listening to music also activates the reward system in the brain, resulting in improved focus and attention. Your favourite songs not only enhance mood by triggering the release of endorphins but also serve as the key to unlocking creativity. As you delve into this melodic journey, remember that music doesn't just sound good – it stimulates large areas of the brain, aids memory, and offers a myriad of positive effects on well-being.

While the benefits of music are undeniable, it’s worth noting that listening to music during work or study may not be a good idea for everyone. For some, the integration of melodies during work or study may divide attention. However, exposure to music in the break, that is, before our work or study, can be a good choice for almost everybody. In a study on secondary school students, researchers found that listening to self-selected music before lessons and during breaks enhances students' mood, motivation, and concentration compared to breaks without music.

Researchers also compared the impact of various relaxation activities such as deep breathing, simply resting without doing any specific activity and listening to music during the breaks. Interestingly, they found out students tended to be more well-rested when listening to any type of music compared to other relaxation tasks, but why? Because listening to music decreases prefrontal activity in students’ brain during the study break. And guess what? No matter what song students selected to listen to, they were most relaxed after listening to their favourite uplifting songs. And here is the twist: listening to Classical music during the breaks activated brain for the next study task. It literally means that by listening to Classical music not only do we have better quality breaks but also better study sessions after the break.

In a nutshell, scientists are suggesting that listening to music, Mozart or your favourite Jazz music, is a promising relaxation technique during study breaks. So, just reach for your headphones next time you are taking a break.

Give the Pomodoro a shot!

The thing is, we are terrible at remembering to take breaks. We end up working for longer hours, and guess what? We're left feeling exhausted.

Longer breaks? Sounds good, but then getting back on track becomes a whole mission.

So, self-regulated breaks? Not working for us (though you can give it a try if you want).

But how about systematic breaks? It turns out some other students invested their time and brainpower to craft a technique just for us.

"Pomodoro technique," coined by Francesco Cirillo in the late 1980s seems to be our solution. It is as easy as it sounds—set a timer, work for 25 minutes, then take a break for a solid 5 minutes. Hit this cycle four times, and reward yourself with a longer 15 to 30-minute break. Oh, and fun fact: "pomodoro" means tomato in Italian 😊.

Researchers have investigated its effectiveness. They have found that self-regulated break-taking leads to less efficient studying, more fatigue, and lower concentration and motivation compared to systematic breaks. Besides, the neuroscientists, Terrence Sejnowski and Dr. Barbara Oakley suggest the use of the Pomodoro technique as a way to alternate periods of focus and diffuse thinking (task-positive and default-mode neural networks, respectively), because the systematic breaks of this technique become a rewarding process.

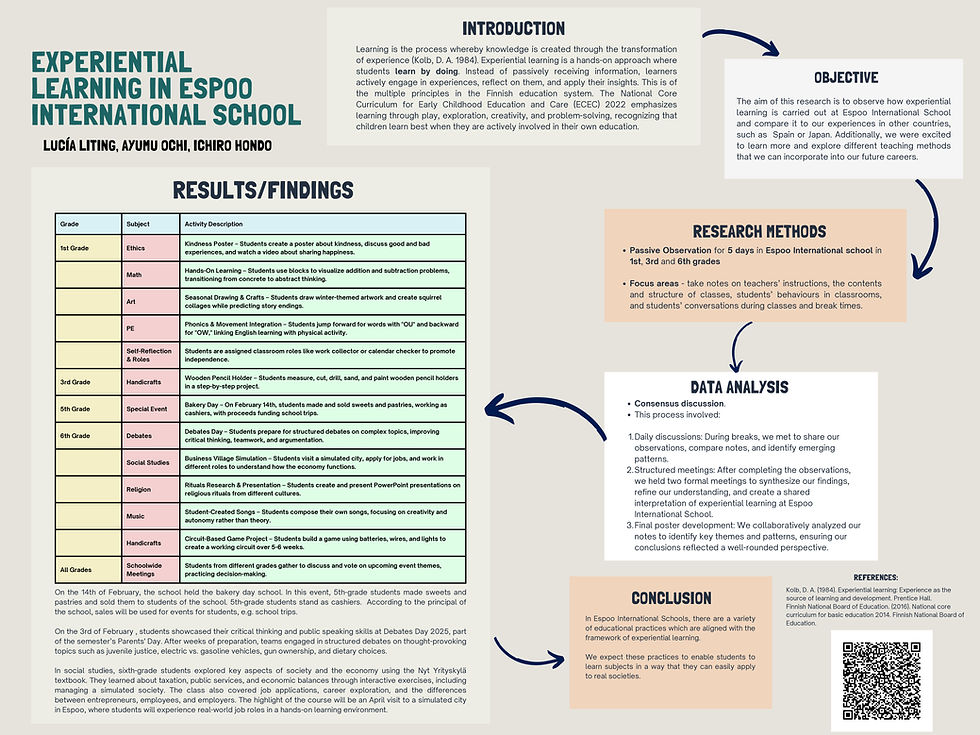

Based on all the above, we designed a writing workshop, combining the Pomodoro technique with physical activity & music breaks.

Click the arrow at the bottom right corner of the above picture to start your workshop now! Hope you enjoy the journey.

Fun fact about this blog:

The blog you are reading now was created following this workshop plan. We piloted this workshop in our long sessions of group discussion and blog writing in the course, Neuroscientific Approach to Artistic and Practical Subjects taught by Minna Huotilainen. We felt more productive, creative, vigilant, and happier! So we highly encourage you to try it out!

Remember to take a break to recharge your brain! 🧡

In case the link in the picture is not working: you can click here:

References:

Basso, J. C., & Suzuki, W. A. (2017). The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plasticity, 2(2), 127-152.

Bennet, A., & Bennet, D. (2008). The human knowledge system: music and brain coherence. Vine, 38(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/03055720810904817

Biwer, F., Wiradhany, W., Egbrink, M. G. O., & De Bruin, A. B. H. (2023). Understanding effort regulation: Comparing ‘Pomodoro’ breaks and self‐regulated breaks. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(S2), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12593

Blasche, G., Szabo, B., Wagner‐Menghin, M., Ekmekçioğlu, C., & Gollner, E. (2018). Comparison of rest‐break interventions during a mentally demanding task. Stress and Health, 34(5), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2830

Chatterjee, R. (2019). Feel Better in 5: Your daily plan to feel great for life. Penguin UK.

Cheng, X., Yuan, Y., Wang, Y., & Wang, R. (2020). Neural antagonistic mechanism between default-mode and task-positive networks. Neurocomputing, 417, 74-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2020.07.079

Hansen, A. (2017). The Real Happy Pill: Power up your brain by moving your body. Simon and Schuster.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(6), 995.

Levitin, D. J. (2014). Hit the reset button in your brain. New York Times, 9.

Maeda, J. K., & Randall, L. M. (2003). Can academic success come from five minutes of physical activity?. Brock Education Journal, 13(1).

McFarland, W. L., Teitelbaum, H., & Hedges, E. K. (1975). Relationship between hippocampal theta activity and running speed in the rat. Journal of comparative and physiological psychology, 88(1), 324.

Moriya, K., Kurimoto, I., Ezaki, N., & Nakagawa, M. (2018). Influences of listening to music in study break on brain activity and parasympathetic nervous system activity. Journal of the Institute of Industrial Applications Engineers, 6(1), 34-38.

Oakley, B., Sejnowski, T., & McConville, A. (2018). Learning how to learn: How to succeed in school without spending all your time studying; A guide for kids and teens. Penguin.

Qi, P., Gao, L., Meng, J., Thakor, N., Bezerianos, A., & Sun, Y. (2019). Effects of rest-break on mental fatigue recovery determined by a novel temporal brain network analysis of dynamic functional connectivity. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 28(1), 62-71.

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., & Ky, C. N. (1993). Music and spatial task performance. Nature, 365(6447), 611-611.

Soysal, Ö., Kiran, F., & Chen, J. (2020). Quantifying Brain Activity State: EEG analysis of Background Music in A Serious Game on Attention of Children. 2020 4th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT). https://doi.org/10.1109/ismsit50672.2020.9255308

Steinborn, M. B., & Huestegge, L. (2016). A walk down the lane gives wings to your brain. Restorative benefits of rest breaks on cognition and self‐control. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 30(5), 795-805.

Sun, Y., Lim, J., Dai, Z., Wong, K., Taya, F., Chen, Y., ... & Bezerianos, A. (2017). The effects of a mid-task break on the brain connectome in healthy participants: A resting-state functional MRI study. Neuroimage, 152, 19-30.

Suzuki, W. (2017) The brain-changing benefits of exercise, Wendy Suzuki: The brain-changing benefits of exercise | TED Talk. Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/wendy_suzuki_the_brain_changing_benefits_of_exercise

Thomson, D. R., Besner, D., & Smilek, D. (2015). A resource-control account of sustained attention: Evidence from mind-wandering and vigilance paradigms. Perspectives on psychological science, 10(1), 82-96.

Vigl, J., Ojell-Järventausta, M., Sipola, H., & Saarikallio, S. (2023). Melody for the Mind: Enhancing Mood, Motivation, Concentration, and Learning through Music Listening in the Classroom. Music & Science, 6, 20592043231214085.

Weber, S., Aleman, A., & Hugdahl, K. (2022). Involvement of the default mode network under varying levels of cognitive effort. Scientific Reports, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10289-7

Wu, Y., Van Gerven, P. W., de Groot, R. H., Eijnde, B. O., Winkens, B., & Savelberg, H. H. (2023). Effects of breaking up sitting with light‐intensity physical activity on cognition and mood in university students. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 33(3), 257-266.

Yanagisawa, H., Dan, I., Tsuzuki, D., Kato, M., Okamoto, M., Kyutoku, Y., & Soya, H. (2010). Acute moderate exercise elicits increased dorsolateral prefrontal activation and improves cognitive performance with Stroop test. Neuroimage, 50(4), 1702-1710.

Young, M. S., Robinson, S. A., & Alberts, P. (2009). Students pay attention! Active Learning in Higher Education, 10(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787408100194

Zou, L., Pan, Z., Yeung, A., Talwar, S., Wang, C., Liu, Y., ... & Thomas, G. A. (2018). A review study on the beneficial effects of Baduanjin. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 24(4), 324-335.

Authors and Contributors:

Güilu Serrano Ferrer: Originally from Mexico, Güilu did her Bachelor’s in Educational Sciences at Universidad La Salle. She is an experienced educator and is interested in how people acquire Spanish as a second language. She is intrigued by the role of procrastination in student’s life as well. She enjoys poetry, learning new languages, long conversations with her family and playing with her dog.

Ying Yang: A second-year Changing Education student, originally from China. Ying loves learning new skills and perspectives. With expertise in instructional design and educational content development, she is passionate about making learning more enjoyable, engaging, and inclusive. In her spare time, she enjoys weight training and immersing herself in nature.

Haomin Wu: Originally from China, Haomin has a background in journalism and applied psychology. Motivated by an interest in developmental psychology, Haomin changed her path to educational science and is now a student in the CE program. She aspires to become an educator who sparks curiosity and helps children discover their passions. In her free time, she enjoys cooking, photographing, and practising piano.

Asiyeh Younesi Asl: While pursuing her studies at UH in Changing Education, Asiyeh has always strived to not only make meaning but also be an active change maker. With roots in Iran, she has lived and worked in the UAE, where multicultural and multilingual environments have nurtured her critical thinking skills, enabling her to consistently seek alternative solutions in education. If not busy studying, she likes exploring Finland, its beautiful scenery and chilling at old coffee spots.

Erika Kadowaki Borgen: Erika has embraced the concept of having many "homes" throughout her journey across various countries. Passionate for education, she has devoted 15 years to shaping minds as a Japanese teacher. Her Bachelor's was focused on Teaching Japanese as a Second Language, showcasing her dedication to language acquisition. She is currently pursuing Master's in Changing Education. Despite the challenges of parenthood, Erika finds solace and joy on weekends with her family, venturing into the woods.

Key Words: Neuroscientific Approach, Breaks, Pomodoro Technique, Master's Thesis Students

Comments